Where the whittling is done

Ernst Karle is preserving one of the Black Forest’s most important traditions. Join us for a story about the last shingle maker in the region.

The journey is an arduous one. Slowly, our car’s plaintive-sounding motor fights its way up the steep and narrow road. Buttercups, dandelions, and poppies bloom off to the side, and lime-green butterflies flutter about in the warm summer air. Suddenly, our driver steps on the brake – hard – just before a hairpin turn. The passenger in the front seat instinctively grabs for the handle above the window. After we nearly scrape past a small barrier, the sight of our gravel-covered parking space comes as a relief. Ernst Karle’s shingle workshop happens to be located 1,100 meters above sea level. On both sides of the road, cows the colour of caramel graze on steep slopes covered in lush green. The tranquil sound of their bells mingles with the chirping of nearby birds. It’s an idyllic scene straight out of a Black Forest picture book.

Ernst Karle stands outside his shingle workshop wearing shorts and a plaid shirt. Along with the ruler and pencil protruding from one short pocket, his hands are clear signs of a craftsman: strong, tanned, and speckled with paint. “Hadn’t cleaned up yet!” he announces with a broad, welcoming smile in his thick local accent. The amiable Karle lifts his glasses from his nose up onto his forehead and urges us into the huge half-timber house. We then find ourselves standing ankle-deep in soft shavings among workbenches and all manner of tools. The floor is completely covered in a fluffy layer of curled wood. “You’ll get the tour in a minute, but coffee comes first.”

Karle has an air of utter calm and satisfaction about him. He sweeps a few wood shavings to the side with one of his shoes, clearing a path to a small counter. Two half-squeezed tubes of mustard lie next to the coffee machine; just behind it, there’s a thick slice of brown bread. I wouldn’t be surprised to see a few smoked sausages hanging from the ceiling, but no such luck. Karle pours cups of coffee before reaching for two small wooden slats – the shingles we also came to see. Your average Jane or Joe, who probably knows little to nothing of wood, will describe any flat piece of the material as a board. Shingles are no different. That’s your first mistake, as Karle explains in the very first minutes of our conversation. “Ois was g’sägt isch, isch a Brett. Ois was g’spalte isch, isch a Schindle.” Rough translation: Anything that’s sawed is a board; anything that’s split is a shingle. This information is essential in manufacturing shingles and will be useful as the day goes on.

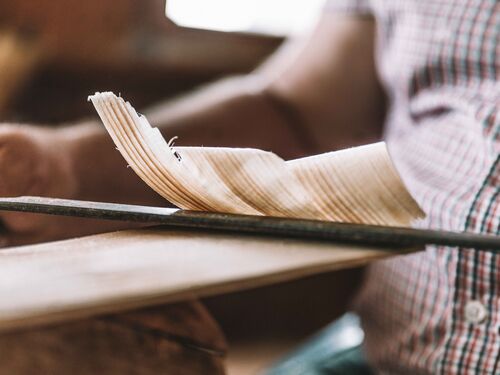

Perhaps further explanation is in order. When a piece of wood is split – that is, divided in two with a hammer and a splitting axe – the separation always runs parallel to the wood’s fibres. The grain of the wood thus remains intact. Sawing wood, on the other hand, cuts through all the fibres, which destroys the structure (and function) of the material. Since wood swells once it becomes wet, the sawed ends of its fibres fray and start to rot. But let’s start from the beginning: What exactly are shingles, anyway? Well, they’re typically used for both roofs and cladding in the Black Forest and other elevated areas of Europe. While they also serve decorative purposes, they mainly keep out the wind and weather.

Shingles are set in an offset manner that resembles the scales of a fish. The way in which they overlap eliminates gaps almost entirely, which is why they’ve proven to be an ideal barrier against biting-cold winds and driving snow for centuries. Every shingle is made and set individually – and by hand. It’s a craft that very few people are keeping alive these days. Indeed, shingle-making has already come this close to dying out forever.

Ernst Karle was born and raised in Muggenbrunn, which belongs to the small Black Forest community of Todtnau. He knows the area’s history and traditions like the back of his hand. Like most people of his generation, Karle’s grandfather was a farmer. He earned his daily bread with a few cows on the sloping meadows – and in particular by working among the trees. Karle can still clearly recall how shingles were always made during the winter, when there was no farm work to be done. Every farming family had the tools (and more importantly, the expertise) required for the job. Times changed, however, and the march of industrialisation eventually arrived in the deepest parts of the Black Forest, as well. Karle’s father learned the masonry trade and began focusing less on farming; traditional wooden cladding fell out of favour, making way for clinker brick. The shingle-making tools once used by his father’s father wound up mothballed in the family’s storehouse.

Ernst Karle himself became a roofer, and the man who taught him the trade had him work almost exclusively with shingles and slate – the time-honoured elements of Black Forest roofs. While the young Karle found it irritating at first, the job shaped his underlying mindset: He gained an understanding of woodworking; respect for the implements involved; and a fundamental knack for finding simple, but precise solutions. Following his apprenticeship, though, shingles were once again forgotten. Roofing tiles were the latest thing, and best of all, they didn’t require tedious manual labour.

During the renovation of his parents’ home, Karle then stumbled upon his grandfather’s old shingle-making tools: splitting wedge, shingle froe, cutting bench. He remembered how he had peered through piles of wood shavings to watch his grandfather put them to work as a young boy. “Reckon I’ll dust these off,” the craftsman mused to himself, and with that, he began making shingles again. Almost immediately, he was inundated with enquiries. “Making shingles, are you? I sure could use some …” Along with the keys to a nearly extinct art, Karle seemed to have discovered a demand that wasn’t being met. He still works with his grandfather’s old apparatus today, and he’s passing the skill onto his son and grandson. “When they’ve got a skill, lots of folks try to keep it for themselves,” he points out. “It’s the wrong way to look at it; you can’t let traditions die!” When he was just starting out, Karle got registered as a wooden shingle maker with the local chamber of commerce and industry. So far, so good – but the time wasn’t quite right, as it turned out. The endeavour met with plenty of enthusiasm, but the orders only trickled in, never amounting to a real breakthrough. Karle eventually became a master roofer who made shingles in his free time. Then, when his son joined the family business and showed interest in his old-fashioned hobby, he could sense that society was changing. “Now’s the time,” Karle recalls thinking, his eyes shining at the memory. “There’s a bit of a shift going on, and people want traditional things again.” The business side has indeed changed for Karle in the past five years. The demand for shingles continues to increase, and making them is now an everyday part of his roofing operation.

In manufacturing a unique product, Karle has found his niche. Experiences from his childhood and teenage years have made him an expert in his chosen field. The actual process of making shingles starts with selecting the right tree. The ones Karle uses are between 100 and 200 years old.

“Finding the right spot is important,” reveals Karle, who favours the spruce trees (the most common variety in the Black Forest) that cover the region’s downwind slopes. Quieter locations like these enable them to grow evenly, which is key to the grain of the wood. Karle shows us the edge of a shingle. “The dark stripes are winter, and the lighter ones are summer,” he explains. Since trees grow less in the wintertime, the dark layers are thinner. Karle makes sure that the light stripes also have the same width. These make up the soft part of the wood and will be washed out by the weather over the course of time. If a tree grows too quickly in the summertime, the resulting light layers will be too thick and cause the finished shingles to rot faster. In addition to a location that allows for steady, deliberate growth, the direction in which a tree has grown is crucial. Karle’s studied eye can immediately tell whether a particular trunk has developed a slight slant or twist. “If the tree has a spiral grain, so will the shingle,” he says. That brings us back to our very first and most important lesson – the one about sawing and splitting. It turns out that Ernst Karle has an infallible feel for wood fibre. He knows exactly how any particular manner of growth will affect his finished product. Meanwhile, his trees of choice grow a bit further up at 1,200 metres above sea level. After consulting the ranger responsible for the area, Karle fells the spruces himself and divides their massive trunks into smaller sections right there in the forest.

We find two prime examples stacked just outside the workshop. Karle transfers his glasses from his forehead back onto his nose and draws his ruler from the pocket of his shorts. After using his pencil to mark the desired width on one of the logs, he coolly jerks the pull cord on his chainsaw. Its diesel motor growls to life, sending several birds flapping away in fright. Karle proceeds to saw a thick, even segment from the wood. “I’ll run and get the splitting axe,” he says before setting the chainsaw down and bounding up the steps to his workshop, apparently without breaking a sweat. A moment later, he returns armed with the axe and a rubber mallet. The outer ring of the trunk at hand is a great deal darker and wetter than the rest. Known as sapwood, this is the youngest part of the tree; it provides the crown with nutrients. “Let’s get that part off,” Karle says as he positions the axe and brings down the mallet. The wood splits apart with a light crack. Karle’s skilful hands remove the sapwood from its exterior. He then places the axe on a small fissure in the middle of the segment’s round, flat surface and swings his mallet once more. Snap! The tree trunk splits into two halves. “There’s a knot right here; no way to see it from the outside,” Karle says, pointing out a curving bulge in the wood. Indeed, the outer surface of the trunk bears no sign of anything that could have been a branch. The next step for our resident shingle expert involves dividing the cylindrical segment into triangle-shaped sections of equal size. “A hand’s breadth of wood will give you about eight shingles, which is good to keep in mind,” he advises. To illustrate the point, he places his hand on the surface of the wood and positions the splitting axe just beyond it. A few more cracking blows of the mallet, and the thick section is divided up like a pie. Karle picks up one of the pieces and marches resolutely towards the workshop.

Once inside, he takes a seat on a low stool and secures the upright wedge of wood between his bare knees. His eyes find the centre point, which is where he sets the axe before bringing the mallet down. The wood cracks again, and Karle repeats the procedure seven more times. Halves, quarters, eighths – all between his bare knees, going by nothing more than his well-trained eye. “Now that we’ve got some shingles, let’s head over to the cutting bench,” he says. In a blink, he’s divided one triangular segment into eight evenly sized panels.

The cutting bench is over near the window, with curly shavings piled up all around. The antique contraption looks a bit like a stylised rocking horse. Karle sits down again and inserts the first shingle. He reaches for a tool with a dark-coloured cutting edge and two handles. Drawing the blade across the wood with a few deft movements, he slices off a few more curls. This makes the shingle a bit thinner and lends it a smooth surface. Karle flips it over and begins stripping away the other side. Two final passes of the blade remove the shingle’s edges to make them even. The entire procedure takes just moments – done, onto the next. On an average day, Karle makes between 500 and 600 shingles.

He needs 140 of them for a single square metre of cladding. That explains the sea of curled shavings. In the meantime, a very fluffy white Persian cat has slunk into the workshop to wind its way around the shingler’s legs with typical feline nonchalance. It’s a lovely scene, if a bit surreal. There’s something almost meditative about the way Ernst Karle makes shingles. His work routines are steady and practised, and every motion of his hands has a purpose. In the background, the cowbells continue their languid jangling.

After the demonstration, Karle drives us to a cabin in the nearby forest. He confidently guides his small lorry around several sharp turns as it rattles its way down the path. We eventually come to a stop at a clearing where the cabin – a small wooden house nearly a century old – has been carefully covered with a green tarpaulin and some low scaffolding. “This wall here is a hundred years old,” Karle says, his fingers following the grain of the dark-brown wooden panels. Another wall has been clad in bright new shingles that will have already changed from light brown to the grey shade typical of spruce by next year. Karle spans a red thread from one side of the wall to the other – a guiding line parallel to the floor – and sits down on the scaffolding. He pulls out his axe, sets down a handful of small nails and two stacks of shingles within reach, and starts hammering. Every panel is fixed in place with no more than two nails. And there he sits, the last wooden shingle maker in the Black Forest, hammering on his wares one after the other as his legs dangle from the scaffolding. “Not bad for a pensioner,” he says with a modest smile. His eyes wander off to the green hillsides and the Feldberg, the highest mountain in the state. “You can even see the Alps today,” Karle adds as he motions towards the snow-covered peaks you can just about make out in the distance. “Can’t imagine doing another job, that’s for sure!” In two weeks, the cabin will be fully clad in wooden shingles. The next job is already lined up, as well – at a parish hall in Nagold (near Stuttgart). Thanks to Ernst Karle and his grandfather’s trusty old tools, a Black Forest tradition appears to be alive and well.